Biodiversity Loss as a Wicked Problem for Business

This article is part of my series on "The Next Economy: Business, Energy & Sustainability in Transition"

Introduction: The vanishing web of life

Nature is unraveling. Across the globe, species are vanishing at unprecedented rates, ecosystems are collapsing, and the intricate web of life that supports human civilization is being steadily degraded. Globally, wildlife populations have plunged by more than 70% since 1970, pollinators are disappearing, coral reefs are bleaching, and forests are retreating. According to a 2019 assessment from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), 25% of all plants and animals, or approximately one million species, are at risk of extinction in coming decades.

Exhibit 1: Species extinction rates

Source: IPBES Report of the Plenary of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (2019)

Biodiversity loss is a systemic crisis with profound implications for food systems, water security, public health, and the global economy. Biodiversity is the invisible infrastructure that sustains life on Earth and the businesses that rely on it. Researchers at the Stockholm Resilience Institute have developed a powerful framework for assessing planetary boundaries. Their research has found that we have already crossed 6 of the 9 boundaries, with climate and biodiversity integrity being core foundations for a healthy planet. Crossing these boundaries increases the likelihood that natural systems will collapse, leading to profound disruptions of the earth’s operating systems.

While climate change has received increasing attention in recent years, biodiversity loss remains elusive. A lack understanding of the problem and its myriad consequences has inhibited a coherent response at scale. The sheer complexity, interdependence, and local variability of natural systems makes biodiversity a uniquely vexing problem for society and business to tackle.

In my own experience working on sustainability at Coca-Cola, it was relatively straightforward to make the case for water stewardship since water was the primary ingredient in everything the company sold. Even though the company relied heavily on nature for ingredients like sugar, coffee, and juices, and clean water depended on healthy watersheds, it was much harder to connect these broader ecosystem dynamics to specific risks or actions required by the company. “Nature” was too abstract for focused corporate action or investment.

Despite this blind spot, companies across sectors do face real existential risks when biodiversity loss threatens supply chains, exposing them to regulatory and reputational risks, and undermining the ecosystems upon which economies depend. As awareness of the crisis grows, there is an urgent need for leadership from companies, to rethink their relationship with the natural world and to contribute to a more resilient, regenerative future.

This briefing explores biodiversity as a "wicked problem" — complex, interconnected, and resistant to simple solutions. It outlines why the crisis matters to business, how leading companies are responding, and what strategic pathways are emerging to navigate this urgent challenge.

What makes biodiversity a wicked problem

Biodiversity loss is not a single issue, but a tangled web of ecological, economic, and cultural processes unfolding in an unpredictable pattern. It often emerges in the contested interface between development and conservation, between short-term profits and long-term planetary health, and between the disparate priorities of diverse stakeholders. These are the hallmarks of a “wicked problem.”

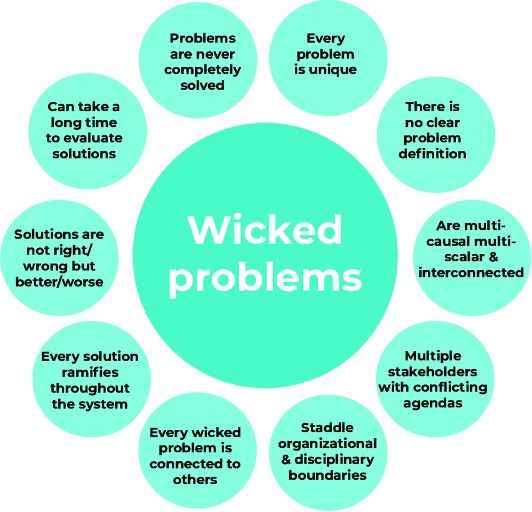

Originally coined in the 1970s by design theorists Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber, a wicked problem is one that defies straightforward definitions or solutions. It is multi-causal, cross-scale, value-laden, multi-stakeholder, and often irreversible. Biodiversity fits this description perfectly.

Exhibit 3. Characteristics of “wicked problems”

Source: Joore, P., et.al. (2019). Teaching Circular Design - Professional Development Course. Research Gate.

First, the drivers of biodiversity loss are deeply interconnected: habitat destruction, overexploitation, climate change, pollution, and invasive species interact in unpredictable ways. Solving one issue can exacerbate another. For instance, biofuel plantations may reduce carbon emissions but accelerate deforestation and displace native species.

Second, biodiversity may trigger conflicts in values between different stakeholders. A wetland may be seen as sacred by Indigenous communities, as valuable real estate by developers, and as essential flood protection by climate scientists. These tensions complicate governance and delay consensus.

Third, biodiversity operates on long, slow timeframes. The full consequences of species loss may take decades to appear, by which time ecosystems may have crossed irreversible tipping points. While the impacts may accumulate gradually, the impacts may spike suddenly across different parts of natural systems.

Fourth, governance is fragmented. No single institution has authority over nature. Global frameworks exist — such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) — but enforcement is weak, and incentives are often misaligned.

In short, biodiversity is a wicked problem because it resists linear solutions. It demands cross-sector collaboration, systems analysis, design thinking, scenario planning, and adaptive strategies — and a commitment to intervene at strategic leverage points. These are the qualities that businesses must learn to cultivate.

Business’ interdependence with and impact on biodiversity

Business is both a driver of biodiversity loss and deeply dependent on nature’s services. Every company — from apparel to agriculture, finance to pharmaceuticals — relies in some way on ecosystems to function. Yet many of these dependencies are invisible, unpriced, or taken for granted.

According to the World Economic Forum, over $44 trillion in economic value, or more than half of global GDP, is moderately or highly dependent on nature. These dependencies include:

Pollination: Critical for agriculture, particularly fruits, nuts, and vegetables.

Water filtration and storage: Essential for industries from beverage production to semiconductors.

Flood protection and climate regulation: Provided by forests, wetlands, and mangroves.

Genetic diversity: The foundation for pharmaceutical discovery and food system resilience.

At the same time, business activity is a key driver of ecosystem degradation. Deforestation for agriculture, land conversion for mining or infrastructure, overfishing, pollution, and globalized trade are accelerating species loss and ecological fragmentation. A few examples:

Agribusiness: The expansion of cattle, soy, and palm oil production drives over 80% of deforestation globally.

Textiles: Cotton and leather sourcing contribute to water stress and habitat loss in biodiversity hotspots.

Extractives: Mining operations often disrupt fragile ecosystems and Indigenous territories.

The impacts cut both ways. As nature declines, risks mount: crop failures from pollinator loss, supply disruptions from water scarcity, reputational backlash over ecosystem damage, and rising costs from regulation or litigation. For businesses, biodiversity is not just a sustainability issue, but an acute strategic concern.

The case for acting on material risks

Until recently, biodiversity was largely absent from boardroom conversations. Climate change commanded attention with its metrics (CO₂), models, and market mechanisms. Biodiversity, by contrast, felt intangible and unmeasurable. That is changing fast.

A growing body of evidence shows that biodiversity loss poses material risks to business — financial, operational, regulatory, and reputational. For example:

Supply chain exposure: Nestlé and Mars have faced scrutiny over cocoa production linked to deforestation in West Africa. Similar risks exist for timber, seafood, and soy.

Physical risks: The collapse of coral reefs and mangroves increases the vulnerability of coastal assets to storm surges and flooding.

Legal and regulatory risks: The European Union’s Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) prohibits the import of commodities linked to deforestation — with fines of up to 4% of annual revenue.

Reputational risk: Fast fashion brands have been criticized for sourcing leather from deforested Amazon regions, damaging consumer trust.

At the same time, new frameworks are helping businesses assess and act on these risks. The emergence of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) is especially significant.

Emerging frameworks for corporate accountability

A key challenge in addressing biodiversity is measurement. Unlike climate change, which can be expressed in carbon equivalents, biodiversity is multi-dimensional and context-specific. However, recent years have seen the development of more sophisticated frameworks to guide corporate action.

Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD)

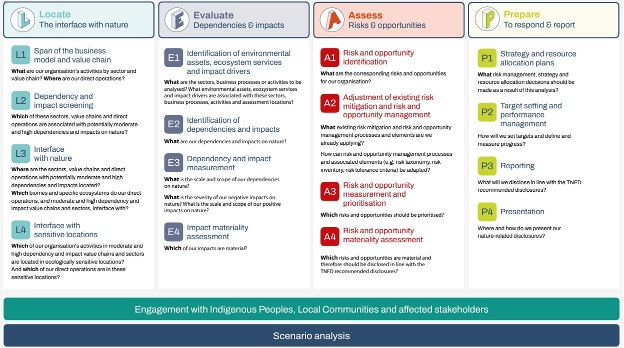

Finalized in September 2023, TNFD provides a standardized approach for companies to assess and disclose their nature-related dependencies, impacts, risks, and opportunities. It mirrors the structure of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), with four pillars: Governance, Strategy, Risk and Impact Management, and Metrics and Targets.

The TNFD also includes the LEAP framework — Locate, Evaluate, Assess, and Prepare — a stepwise guide to integrating nature into risk management and reporting. Sector-specific guidance has been released for industries including apparel, agriculture, and construction, with more forthcoming.

Exhibit 2: TNFD’s LEAP (Locate, Evaluate, Assess & Prepare) Framework

Source: Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures, 2023

Science-Based Targets for Nature (SBTN)

SBTN, an extension of the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), offers companies a way to set quantifiable targets for nature, including freshwater use, land conversion, and species loss. Pilots are underway, and full adoption is expected in the next two years.

CSRD and ESRS E4 (EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting)

Under the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), companies must report on biodiversity impacts using the ESRS E4 standard, based on a principle of double materiality — how biodiversity affects the firm, and how the firm affects biodiversity. This is driving deeper integration of biodiversity into corporate disclosure across Europe.

These frameworks are not just bureaucratic requirements. They represent a shift in how business value is defined — from financial-only to nature-inclusive. Leading firms are aligning their strategies accordingly.

Corporate leaders taking action

A growing number of companies are moving beyond compliance toward proactive biodiversity strategies. While many initiatives are still early-stage, several stand out.

Orsted: Ørsted, a global leader in offshore wind energy, has committed to achieving a net-positive biodiversity impact for all new renewable energy projects commissioned from 2030 onwards. This means that each project will contribute more to biodiversity than it takes away, through proactive restoration and conservation efforts. To realize this ambition, Ørsted is pursuing a partnership with ARK Nature to restore shellfish reefs and other marine habitats in the North Sea to enhance ocean biodiversity. The company is also developing a framework to measure, track, and report on biodiversity impacts, ensuring transparency and accountability in their efforts to achieve net-positive outcomes.

IKEA: Through its Forest Positive Agenda, IKEA plans to plant 1 billion trees by 2030. It is also working to improve biodiversity outcomes in its global supply chain, including restoring degraded forests in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia.

Kering: The French luxury group was the first in its sector to adopt science-based targets for nature, focusing on land use, water, and ecosystem integrity. In Tuscany’s Arno basin, Kering works with Indigenous communities to ensure Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) in leather production. The group has also launched an open-source biodiversity impact tool for the fashion sector.

GSK: By 2030, pharmaceutical giant GSK aims to deliver positive biodiversity outcomes across all owned sites. This includes habitat restoration, pollinator gardens, and deforestation-free sourcing of all agricultural inputs.

Unilever and Danone: These consumer goods giants are core members of the Business for Nature coalition, calling on governments to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030. Both are investing in regenerative agriculture, working with farmers to rebuild soil health, diversify crops, and reduce chemical inputs.

These cases show that while risks are real, so too are opportunities. Companies that act early can shape regulatory frameworks, build consumer trust, and secure long-term access to natural capital.

Charting a strategic response

What does a credible biodiversity strategy look like? While each sector will vary, several principles are emerging:

1. Follow the Mitigation Hierarchy: Avoid harm first, then minimize, restore, regenerate, and finally transform systems. This sequence mirrors the “reduce-reuse-recycle” of biodiversity — but with more emphasis on avoiding irreversible damage.

2. Invest in Nature-Based Solutions (NbS): From wetland restoration to agroforestry, NbS deliver measurable biodiversity gains while offering climate and water co-benefits. They are often cost-effective, locally empowering, and brand-enhancing.

3. Engage the Full Value Chain: Most biodiversity impacts occur upstream — in agriculture, fishing, mining, and forestry. Businesses must work with suppliers to embed biodiversity criteria into procurement and sourcing.

4. Measure What Matters: Metrics like Mean Species Abundance (MSA), Potential Disappeared Fraction (PDF), and the Corporate Biodiversity Footprint (CBF) are emerging as tools to assess impact. These are still evolving but offer a starting point for action.

5. Make It Local: Biodiversity is always place-based. Strategies must reflect local ecological conditions, cultural values, and regulatory contexts. Partnerships with Indigenous communities and local NGOs are essential.

6. Think resilience and regeneration: It is not enough to do less harm. Businesses will need to create business models and strategies that reverse damage and restore ecosystems to healthy functioning. For example, Patagonia Provisions partners with regenerative farms and fisheries to source ingredients like regenerative organic grains and grass-fed meats. These partnerships promote agricultural practices that build soil health, sequester carbon, and restore ecosystems, while supporting small-scale producers.

Conclusion

The biodiversity crisis is real, global, and accelerating, but it is not inevitable. For businesses, this moment demands more than pledges and partnerships. It requires urgency and a strategic mindset shift.

Companies must move beyond the mindset of "do less harm" toward actively regenerating the natural systems on which they depend. That means integrating biodiversity into risk assessments, supply chains, product design, and governance structures. By investing in data, partnerships, and innovation, companies can connect the dots between their long-term business success and the health of the planet.

For those interested in learning more about the business of biodiversity, see Emily Purcell’s briefing “Biodiversity & Business: What Every MBA Needs to Know” in our MBA EDGE series.

Disclosure: Portions of this document were generated or refined using ChatGPT, with original insights and editorial oversight by the author.