Class 1 Recap: Managing Tensions Between Profits and Purpose

Part of my insider series tracking the conversations in my MBA course "Climate, Sustainability, and Corporate Governance"

On September 5, we kicked off Climate, Sustainability, and Corporate Governance (CSCG 2025) with a session framing one of the central tensions of the course: how can businesses reduce risk and pursue profit while respecting planetary boundaries and societal expectations? The classroom was full, with 75 mostly 2nd year MBAs tacking some of the most important challenges facing business and the world.

Setting the Frame

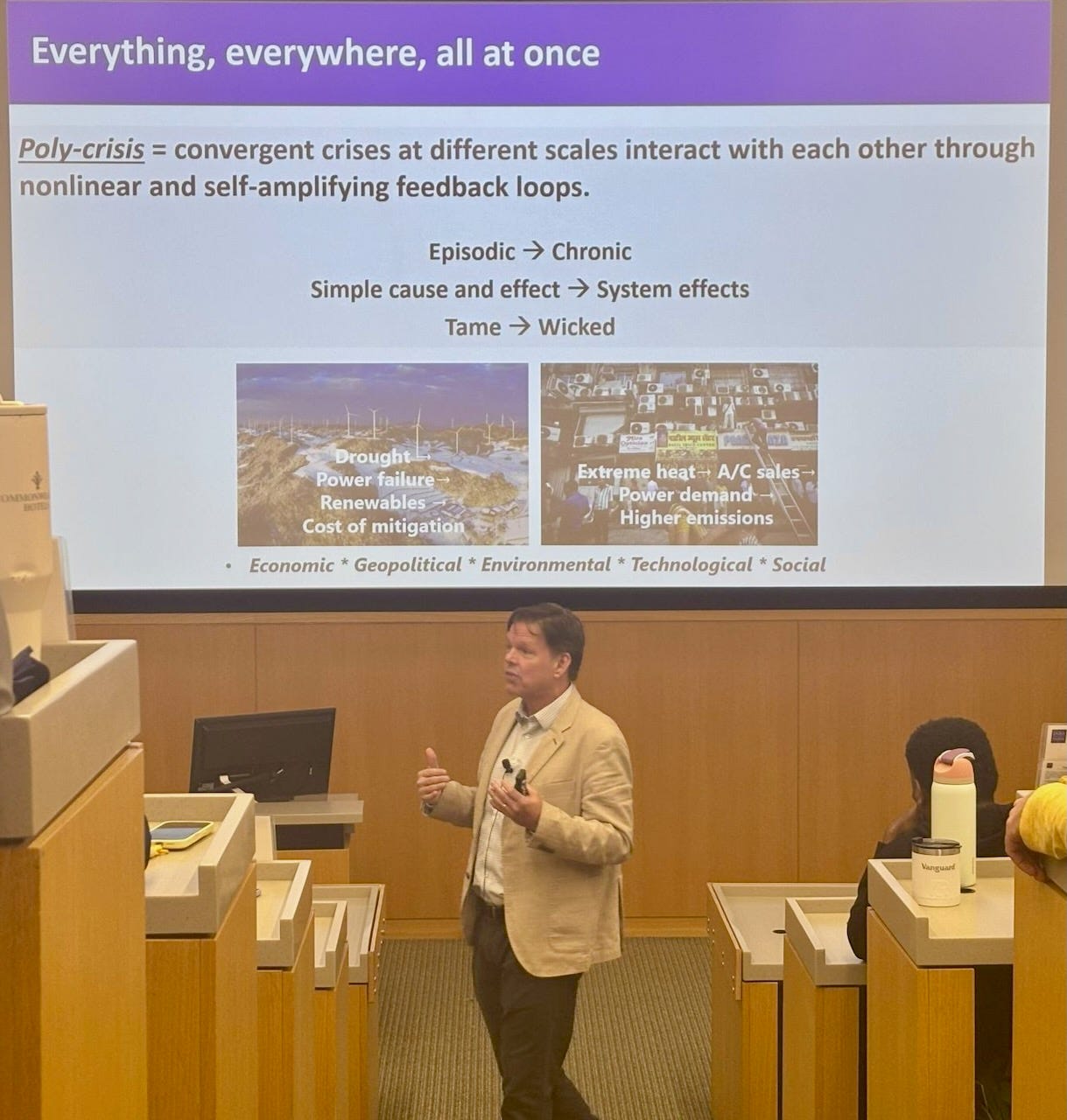

Our starting premise is that growing human populations, GDP growth, and resource consumption have created uniquely challenging dynamics for businesses in the 21st century. With a global economy now almost 40 times larger than 1925, we are pressing on or crossing ecological tipping points, or “planetary boundaries” – everywhere. The convergence of multiple crises - environmental, geopolitical, economic - is creating a “poly-crisis” which has profound implications for business strategy, risk, and competition.

At the same time, while we have made great progress in meeting human needs for food, water, energy, and infrastructure, we still face daunting challenges in enabling 8 billion people to thrive in coming decades. The collision of human needs on a full planet and the escalating disruption of ecological systems is now a central strategic dilemma. What is the role of the private sector in creating global economies that operate in the “doughnut” (see Kate Raworth) between human development and the ecological ceiling?

The Starbucks $7 Latte case provided a rich context to explore this issue. At face value, it’s a story about managing risk for a ubiquitous global brand. But looking deeper, it is obvious that climate change is already creating material costs that play out through much of their supply chain and business model. And most of this cost is not driven by regulatory efforts; it accumulates through commodity volatility, store utility costs, and investment terms.

Who Pays for Climate Risk?

The discussion opened with a straightforward but provocative question: Does the $7 latte reflect the real costs of climate risk? Students immediately jumped in with differing views.

A few argued that the retail price has little to do with ecological realities. The $7 covers labor, beans, and brand premium—but not carbon emissions, deforestation, or water stress. Those costs, they said, are effectively pushed off the balance sheet onto farmers, governments, and future generations.

Others suggested that some costs are indirectly embedded or internalized through rising commodity prices during drought years or insurance premiums that reflect more volatile supply chains. They conceded, however, that this is a lagging, partial adjustment rather than a true reflection of risk.

One student raised the point that by the time consumers face higher prices, the damage has already been done upstream. The burden lands first on farming communities, who are the most vulnerable and least able to absorb shocks.

Another observed that climate costs eventually circle back into society in the form of taxpayer-funded disaster relief or development aid. In that sense, we’re all subsidizing the latte, whether or not we drink it.

We also had a spirited debate about whether insurance is an effective tool for companies and individuals to manage climate risk, giving a backstop to increasing vulnerability. In general, many students noted that insurance is most effective in distributing unpredictable risks across a pool, and were skeptical about the efficacy of insurance to manage the increasingly chronic and predictable impacts of climate change.

This prompted a sharp exchange over who should pay the price for climate damage. Should Starbucks voluntarily internalize climate costs into its pricing and sourcing strategy, even if the market doesn’t demand it? Some thought yes—because credibility and resilience require it. Others pushed back: if Starbucks does so unilaterally, would it make them more resilient than rivals who don’t, or does this cost undermine their ability to compete? That tension—between acting ahead of regulation and waiting for the “level playing field”—surfaced as a real strategic dilemma.

Evaluating Strategic Options

From there, the class shifted into a second, equally challenging question: If Starbucks is going to act, how should it decide which options are best? In the case, Starbucks has decided to invest $100 million in sustainability efforts, but had to choose between four options:

1. Climate-resilient coffee: expanding seedling distribution and farmer loans.

2. Greener Store retrofits: expedite 1,000 additional stores this year.

3. Cup Re-use roll-out: take a local initiative to reduce plastic waste, and scale it nationally.

4. Supplier-finance facility: low-interest loans and long-term contracts for dairy and coffee partners.

Our initial question was to explore whether $100 million was an adequate strategic investment in sustainability, and how you might assess what an appropriate investment might be. We brainstormed several different approaches – basing investment on Starbucks’ profits, revenue, or greenhouse gas emissions – but generally concluded that the intended investment was inadequate for a company like Starbucks.

The conversation then shifted to identifying the most salient criteria for assessing the company’s strategic options. We posted several candidate criteria on the board, and then considered which would be most valuable for selecting the most effective option, including:

Profitability. Several students argued that any serious strategy must protect the bottom line. The basic logic was that if an initiative erodes margins too far, it won’t survive. We also discussed the pros and cons of using Internal Rate of Return (IRR) vs. Net Present Value (NPV) for this calculation, and whether both were needed.

Emissions Impact: A second group highlighted the importance of emission reductions, as this was the key environmental metric they were attempting to move.

Reputation and Brand. Others countered that Starbucks’ competitive advantage lies less in price than in brand identity. Investing in sustainability - even at a cost - could pay dividends in trust, authenticity, and customer loyalty.

Material Risks. Another group emphasized operational continuity: without water security and resilient farmers, there is no coffee business. These students argued that Starbucks should focus on initiatives that directly safeguard the supply chain.

Broader Impact. Some voices insisted that criteria must extend beyond company-centric concerns: reducing inequality among farmers, protecting biodiversity, and addressing community needs. Limiting evaluation to financial and brand metrics would miss the point.

Feasibility and Scalability. Finally, pragmatic perspectives reminded the group that not every good idea can be implemented effectively. Starbucks should weigh whether an option can be scaled globally and measured credibly to withstand scrutiny from investors and NGOs.

As these perspectives collided, students wrestled with trade-offs. By the end, there was no single answer—but there was consensus on one point: the criteria themselves are a governance choice. They reveal what kind of company Starbucks wants to be, whose voices it listens to, and how it defines value.

Closing Thought

Our first session showed that businesses can no longer afford to treat sustainability as external to strategy. Every decision - about pricing, supply chains, governance, or innovation - is entangled with environmental and social systems. The $7 latte forces us to ask: what world are we really buying into?

The latte case reminded us that every purchase—and every corporate decision—carries hidden costs. The real price tag of coffee isn’t printed on the menu board, but it’s showing up in our climate, our communities, and our future.

Amazing!! Great thinking to include and discuss the decision framework. This is sound decision-making process in action for the students. Thanks for sharing!!

Wow, what a great class, Dan! I particularly loved the criteria the class established because that's clearly what will matter long-term. to any given company or corporation. Thanks for this excellent summary, and I look forward to the synopses of future classes.