Class 10/11/12 Recap: Designing the Future — Innovation, Integrity, and Individual Impact

Part of my insider series tracking the conversations in my MBA course "Climate, Sustainability, and Corporate Governance"

Thanks for all of you who have joined us on this journey at the intersection of business strategy and sustainable impact. These last 3 courses move our conversation forward from the specific cases and topics of corporate sustainability toward broader questions of value creation, corporate purpose and governance, and personal approaches to societal change.

The students in this course have been among the most engaged in recent years - a source of real encouragement and hope for me during this otherwise dark period. I have heard countless stories from my students about fresh insights, shifts in interests and priorities, and inspiration for new career directions. Seeing this tangible, personal impact in the lives of my students is the best part of my work - and I truly appreciate the opportunity to curate that process.

Here are the highlights of our last 3 classes:

Class 10 – Building Innovation Ecosystems: The Iceland Ocean Cluster

We began by exploring what it really means to build an innovation ecosystem. I framed the conversation around the idea that innovation ecosystems form in the spaces where ideas, capital, and culture come together. The Iceland Ocean Cluster shows what happens when collaboration itself becomes part of the national DNA. Its guiding vision of “100 percent fish” isn’t just a clever slogan about waste reduction - it’s a wholesale re-imagining of value and purpose.

Guest speaker Thor Sigfusson, joining us from Reykjavík, described how the movement began: “We used to throw away half of every fish we caught. Today, we use almost all of it - collagen, oil, skin, bones, enzymes, even fish leather.” He emphasized that the breakthrough wasn’t technological but relational: “What makes it work is trust. We meet every day, share data, and sometimes even customers. It’s not about one big company. It’s about 120 small companies learning from each other.” When fishermen, engineers, and artists started sharing the same space, he said, “innovation happened fast.”

Thor Sigfusson, Founder and Chairman, Iceland Ocean Cluster

Students quickly picked up on the role of scale and culture. One asked whether the model succeeded precisely because Iceland is small - “How could something like this scale in a place like the U.S.?” Another wondered about government’s role: “Did policy help build the cluster or just stay out of the way?” A third challenged the assumption of perfect cooperation: “You talked about sharing knowledge openly - how do you avoid free-riders who take ideas but don’t contribute?” Others linked the story to broader sustainability frameworks, noting that the cluster functions like a regenerative system, each part feeding the others rather than competing.

Thor acknowledged that exporting the model isn’t simple: “We’ve tried to share this in Namibia, Norway, and the U.S., but culture matters. You can’t copy-paste trust.” That remark prompted reflection on how ecosystems are rooted in local relationships yet can inspire global learning.

I closed the discussion by observing that ecosystems are living systems - they require constant tending. You can’t manage them the way you’d manage a firm; you cultivate them. What makes the Iceland Ocean Cluster remarkable is not just its efficiency but the alignment of purpose, profit, and place - a reminder that leadership in innovation often means designing the conditions for creativity, not just the products that emerge from it.

Class 11 – Leading Systems Change: Patagonia’s Strategic Pivot

We opened with the story that captured headlines worldwide: Yvon Chouinard’s 2022 decision to transfer ownership of Patagonia to a nonprofit trust so that, in his words, “Earth is now our only shareholder.” I reminded the class that this case wasn’t just about a governance mechanism; it was about a re-imagining of capitalism itself. Patagonia forces us to ask what happens when the moral and financial logics of a company finally point in the same direction?

Students quickly dove in. One observed that the move worked because Patagonia had decades of credibility to build on; another countered that success itself made the decision possible - “it’s easier to be virtuous after you’re profitable.” A third student pointed out how the trust model insulated Patagonia from shareholder pressure while still keeping it accountable to its mission. That comment led to a lively back-and-forth about whether purpose trusts could work in public markets or whether they’re inherently a privilege of private ownership.

The conversation deepened around the mechanics of change. We unpacked how the Patagonia Purpose Trust holds all the voting stock while the Holdfast Collective receives the profits for environmental protection. Several students said this bifurcation reminded them of dual-class shares used for control, but with ethics rather than ego at the center. One asked pointedly, “Could this structure survive a future leadership team that doesn’t share Chouinard’s values?” That question brought us to culture as the ultimate safeguard. Governance can lock in intentions, but culture carries them forward. We all had a brief discussion of the merits and limits of other governance arrangements like B-corps, benefit corporations, and company-affiliated foundations. In summary, most students were interested in these alternative forms of governance, but were skeptical about the current efforts to reorient capitalism toward positive societal outcomes.

We closed by stepping back to the broader theme of the course: leading systems change. I told the group that what makes Patagonia radical isn’t its tax structure but its imagination, its willingness to redesign ownership around planetary stewardship. Our final reflection circled this question: If you could redesign the rules of your organization, what would you optimize for growth, resilience, justice, or regeneration? It seems that tradeoffs are inevitable, though Patagonia’s example suggests it is an experiment worth continuing.

Class 12 – Designing Your Theory of Change

Our final session brought the course full circle, from systems thinking and corporate cases to personal agency and leadership intent. I opened by reminding the group that sustainability strategy ultimately demands a theory of change: a clear logic for how one’s actions contribute to outcomes beyond the firm. It’s easy to critique systems but it’s harder - and more useful - to map out how you will personally move them.

Students presented their personal Theories of Change in short talks, each grounded in a sector, role, or problem. One student began by reflecting, “I used to think my work would change the world by scaling new technology. Now I see it’s as much about who I can bring with me.” Others focused on impact through finance, storytelling, or governance, bridging personal values and strategic leverage points.. Many students described the struggle between systems change and the imperative to narrow focus - choosing one issue, one action, one place to start.

We reflected on the evolution of our conversation across the term—from diagnosing planetary crises to imagining regenerative systems, and finally to defining our personal agency within them. The exercise reminded us that sustainability isn’t an external problem to be solved, but a practice of alignment between values and action. Theories of Change are living maps that evolve as experience deepens.

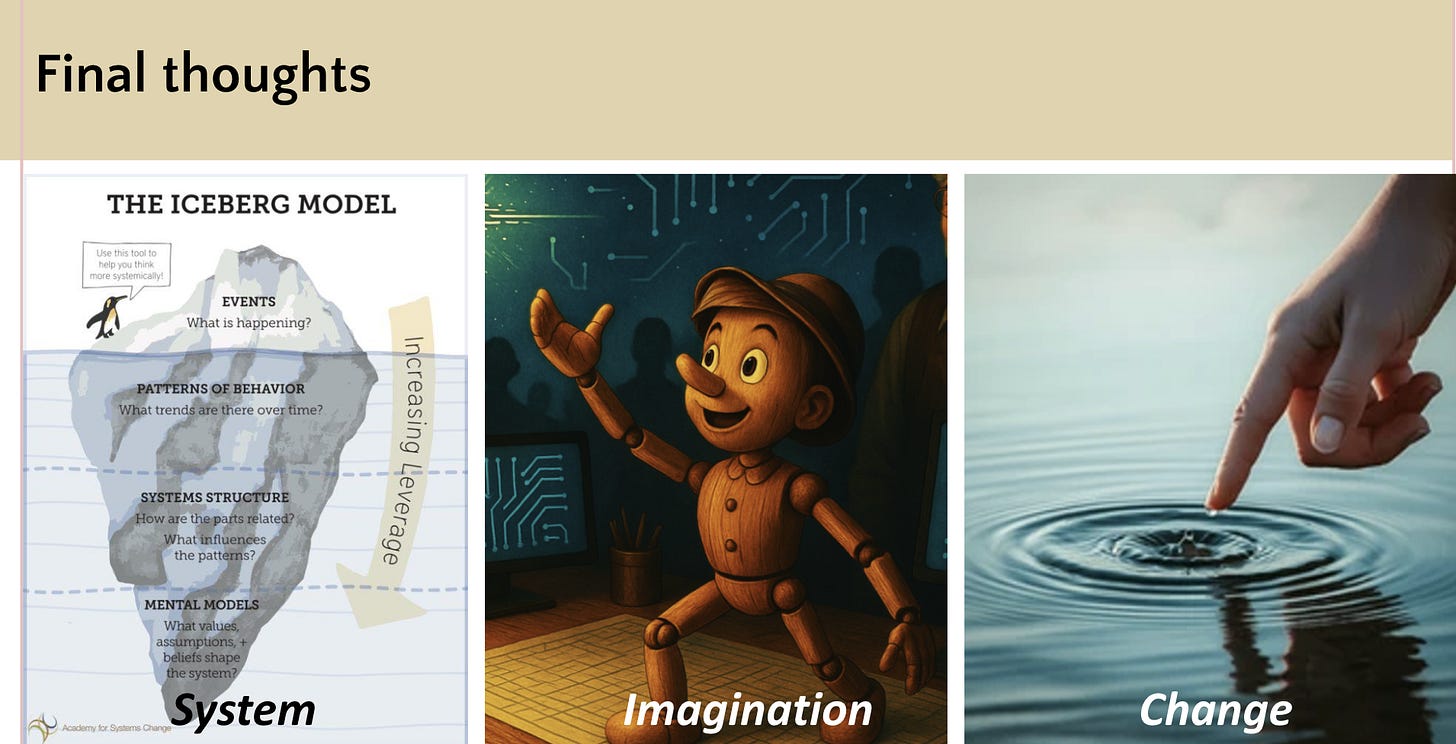

As we reached the end of our final class, I invited students to keep three images in mind: first, I showed a picture of an iceberg, and encouraged the students to always seek to understand the dynamics below the headlines, to track the tectonic plates more than the daily weather. Second, I shared a picture of Pinocchio, who wished on star to become a real boy. I used this example to encourage students to dare to imagine, even when the current environment is filled with negativity. I also reminded them to hold on their honesty and integrity, avoiding Pinocchio’s fate when he wasn’t truthful. Finally, I shared a photo of a hand sending a ripple out on a pond. The reference here is to seek to make an impact (the ripple), but to have fun playing in the water, and don’t take yourself too seriously.

Thus ends our journey. I hope you continue to stay in our conversation. We have so many more mountains to climb, adventures to pursue, insights to discover.

So great to hear how engaged and inspiring the students were in your course, Dan. We all need that. Keep up this important work; we're following your writing.

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot. The Iceland Ocean Cluster is inspireing. What if this '100 percent' mindset scaled beyond fisheries? Imagine urban ecosystems with near-zero waste, driven by collaborative innovation. That's the paradygm shift we truly need.