Class 8 and 9 Recap: From Peanut Butter to Planetary Systems

Part of my insider series tracking the conversations in my MBA course "Climate, Sustainability, and Corporate Governance"

Class 8 – Big Spoon Roasters: Purpose in Practice

Our visit to the headquarters of Big Spoon Roasters in Hillsborough, NC offered a rare inside look at how a small, values-driven business turns sustainability from principle into practice. Students toured the local production facility, watching as staff carefully weighed the day’s waste—usually just a few pounds—to uphold the company’s zero-waste commitment. They saw how employees scraped the last bit of nut butter from mixers to donate to local food programs and even analyzed the trade-offs between reusable and compostable tasting spoons, balancing water use against waste.

In conversation with founders Megan and Mark Overbay and their team, students encountered a company that treats every operational choice as an ethical one: whether to sell through grocery stores or maintain direct relationships with customers; how to verify supply chains for ingredients like cashews and vanilla; and whether selling through Amazon undermines or extends the mission. These choices illuminated the tensions between scale and integrity, growth and control, profit and purpose.

During the class debrief, students described Big Spoon as a living example of values-based entrepreneurship—where culture, authenticity, and product quality reinforce one another. Employees clearly loved their work, and their pride translated into brand credibility. Yet the discussion also surfaced the company’s structural limits: the difficulty of tracing supply chains, the ambiguity of certifications, and the lack of universally accepted sustainability standards.

One person compared the current state of sustainability reporting to financial accounting a century ago: “There were no consistent rules, no shared metrics—just a lot of improvisation.” The class agreed that building such standards is part of the generational work ahead. Big Spoon’s experiment in moral clarity, they concluded, shows what integrity looks like before the systems exist to measure and reward it.

Class 9 – Norges Bank Investment Management: Capital and Credibility

The following session shifted from local craft to global capital, using the Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM) case to examine how the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund—managing more than $1.8 trillion - balances long-term returns with systemic sustainability challenges.

Students who had visited NBIM’s headquarters in Oslo during the Nordic GATE program described a paradoxical culture: understated offices and quiet discipline masking enormous financial power. They recalled how employees combined technical expertise with optimism—seeing their work not just as managing assets, but as stewarding the future.

To frame the discussion, students mapped different investor types - from impact funds to private equity - along two dimensions: influence (market power) and commitment to sustainability. On that grid, NBIM emerged as a high-influence, mid-commitment actor: a universal owner with global reach but limited freedom to deviate from financial benchmarks. The class explored how its five-layer governance structure and 1.25% capped tracking error constrain its ability to act boldly, even when its leaders want to.

Debate then turned philosophical. If NBIM profits from companies developing adaptation or resilience technologies, is that ethical investment or disaster capitalism? Can capital markets truly finance regeneration, or only profit from crisis? Students disagreed but acknowledged that NBIM’s structure—public, transparent, and globally diversified—makes it a mirror of the system it seeks to change.

Discussion of its top holdings - Microsoft, Apple, Google, NVIDIA, Meta - sparked questions about whether the fund’s portfolio reflects the economy’s actual sources of value or simply its financialized perception of it. Some argued that NBIM’s greatest leverage lies not in divestment but in soft power—its ability to influence norms through engagement, its widely read Responsible Investment Report, and CEO Nicolai Tangen’s In Good Company podcast, which amplifies conversations about corporate accountability.

Professor Vermeer framed the case as a test of systemic leadership: How can an investor bound by political mandates and market rules still shape a more sustainable economy? The answer, students noted, may not be found in “what” NBIM invests in but “how” it wields its influence.

Guest Lecture – Professor Fern Wickson and the IPBES Transformative Change Assessment

The class culminated in a guest session with Professor Fern Wickson, ecologist and sustainability scholar at the University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway, who joined to discuss the landmark IPBES Transformative Change Assessment (O’Brien, Wickson et al., 2025).

Wickson began with a grounding exercise: “What do you love about being alive on planet Earth?” Students named oceans, mountains, seasons, and mystery—reminders of what sustainability is meant to protect. She then outlined the “triple planetary crisis”—climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution—and presented stark statistics: a 73% decline in global wildlife populations since 1970, and the risk of losing nearly all coral reefs if warming exceeds 2°C.

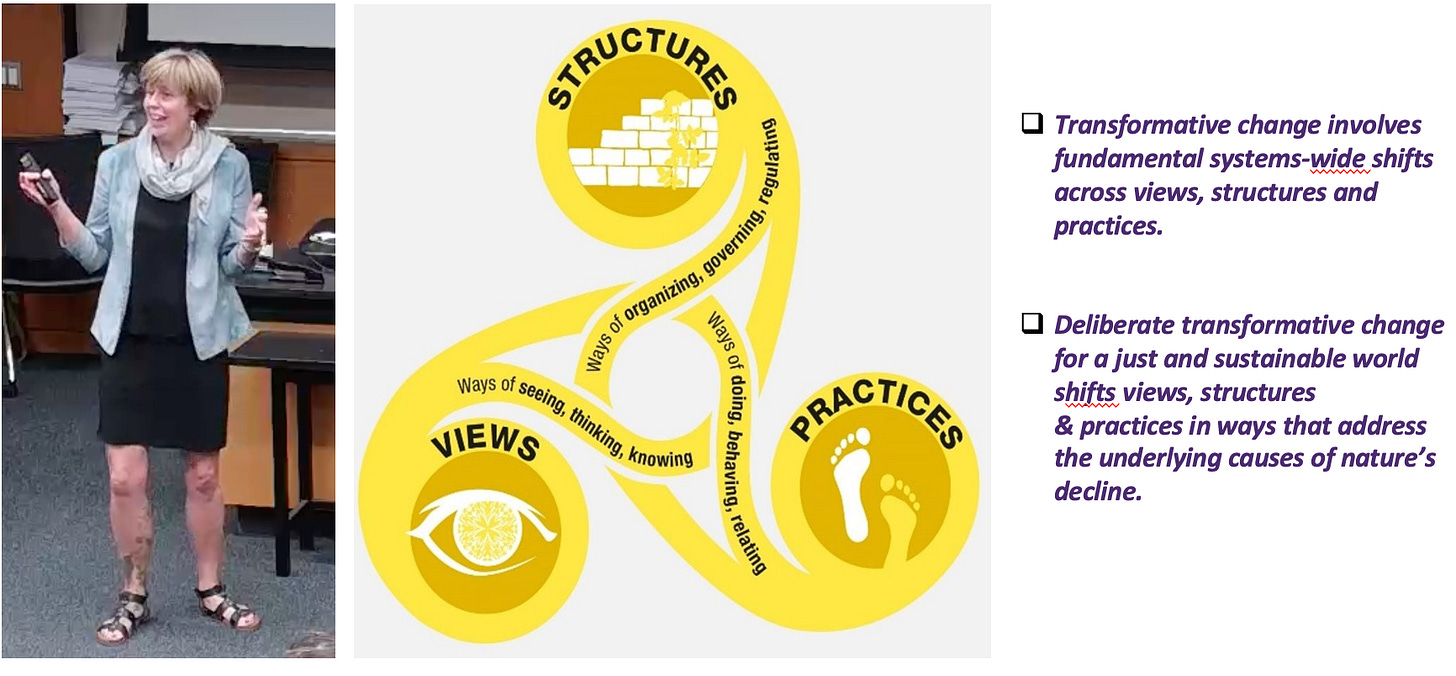

Yet Wickson’s message was not despair but transformation. Drawing from the IPBES framework, she defined transformative change as systemic shifts across three interconnected dimensions:

Views – how we think, value, and imagine;

Structures – how we govern, regulate, and allocate power;

Practices – how we act and relate to one another and to nature.

She identified three root causes of ecological decline: disconnection and domination, concentration of wealth and power, and the prioritization of short-term material gain. To reverse them, she argued, societies must embody four counter-principles: equity and justice, pluralism and inclusion, reciprocity with nature, and adaptive learning.

Using ecological metaphors, Wickson described how existing systems must decompose before new ones can grow, urging students to see themselves as “seed planters” preparing ideas and institutions for emergence when the old order fails. Transformation, she noted, is not only structural but imaginative—requiring us to envision what thriving human–nature relationships could look like.

A rich dialogue followed. Wickson and Professor Vermeer discussed “future design” experiments—decision-making processes where some participants represent future generations—and “Council of All Beings” exercises, where participants speak on behalf of nonhuman species. Both invited students to practice moral imagination as a form of leadership.

In response to a question about working within the U.S. business context, Wickson offered pragmatic encouragement: “Systems must break down before they renew. The work is to cultivate the seeds of what comes next—and to do it in community, not alone.”

Synthesis – Connecting the Micro and the Macro

Together, these two sessions traced the full arc of sustainability—from the tactile integrity of a small Durham factory to the strategic influence of a trillion-dollar fund. Big Spoon Roasters showed how purpose can animate everyday decisions but strain against financial limits. NBIM revealed how global institutions can drive systemic change yet remain constrained by governance, politics, and market inertia.

Professor Wickson’s IPBES framework provided the bridge between them: both the small entrepreneur and the sovereign fund operate within systems that must evolve across views, structures, and practices. Big Spoon is changing culture from the ground up; NBIM, from the top down. Both are necessary, and both are incomplete.

In the end, the question uniting Classes 8 and 9 was not simply how to make business sustainable, but how to make sustainability transformative—turning purpose from a moral stance into a design principle for the next economy.

Reference

O’Brien, K., Wickson, F., et al. (2025). IPBES Transformative Change Assessment: Summary for Policymakers. Intergovernmental Science–Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Zenodo.