Recap of Class 4: Managing Risk and Scaling Impact (Water)

Part of my insider series tracking the conversations in my MBA course "Climate, Sustainability, and Corporate Governance"

Water, Basin Logic, and Corporate Governance

If you have been following our Climate, Sustainability, and Corporate Governance (CSCG) class so far, you know that we have covered the foundational concepts of corporate sustainability and are now exploring the fundamental areas of focus in the field: energy, climate, food, and water. After an initial debrief of the previous session, this class session focused on water scarcity and risk management by emphasizing the river basin as the correct unit of analysis, rather than a single facility.

The discussion moved from first principles—such as the success of upstream conservation efforts in the Catskills—to complex managerial choices related to governance and corporate strategy, including a review of the Coca-Cola case study. A central theme was that water issues are driven by institutional failures and misaligned incentives as much as by hydrology, leading the class to conclude that effective strategies must shift capital upstream toward watershed restoration and collaborative action, away from simple, often inadequate, plant-level metrics. Ultimately, the session stressed that corporate sustainability requires adopting system-level logic and governance structures to address shared basin problems.

The class session served as a transition from the prior climate risk discussions to focusing on water as a fundamental, strategic business issue, using Coca-Cola's water strategy as a core case study. The session moved from debriefing a complex organizational transition exercise to establishing the local nature of water risk, the water-energy nexus, and finally, analyzing corporate managerial choices in high-stress basins.

1. Debrief on Prior Assignment (EcoManufex)

The instructor noted that the students outperformed expectations on the previous multi-stage transition plan assignment for the fictionalized company EcoManufex. The exercise's main highlight was demonstrating that climate risk includes both physical and transition risk and requires rigorous analysis to evaluate risk reduction and value creation opportunities. On the way out of class, student A observed that she was stunned by the degree of “business integration” now required of firms to compete in a climate-impacted market environment, noting that the rhetoric is moving past the "feel good qualitative" stage.

Student Insights on the in-class exercise:

· Role-Playing and Perspective: Student B found it intriguing that people made convincing arguments based on their assigned role, even if they did not personally believe in the argument. Student C, who played the CEO, felt the challenge of hedging different opinions and trying to find the best compromise while acknowledging that "nobody was really going to be happy" with the full path taken.

· Internal Dynamics: Student C also noted that procurement was central to their business’ decisions, suggesting internal dynamics that influenced which opinions mattered more.

· Marginalization: Student D, who played the employee representative noted feeling marginalized, observing that by the end, "no one was listening".

· Shifting Priorities: Student E (the CEO with a technical background) was initially focused strictly on profit and delivery but was surprised and found it interesting to hear the justifications from the Chief Sustainability Officer (CSO) regarding carbon footprint.

· Clarity and Collaboration: Student F highlighted that the CEO setting clear priorities upfront (three priorities) helped the group collaborate better and return to the goal when they got off track.

· Physical and Transition Risk: The class established that the heart of the prior assignment was quantifying climate risk. This involves recognizing that most people conflate climate risk with only physical risk (e.g., floods, droughts, supply chain failure).

· The instructor emphasized that the "lurking risks" are often multiple times more important, specifically transition risk, including policy and regulation (like the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism or California's Cap-and-Dividend system), technology and market shifts (e.g., EVs replacing internal combustion engines), and investor/consumer pressure (e.g., BlackRock integrating climate risk).

· Emerging Risks: The discussion also touched on liability and litigation, noting that attribution science now allows linking specific company emissions to the cost of certain disasters (like Hurricane Helene).

· Carbon Leakage: Student G raised the macroeconomic concern that stringent accountability in Western countries could lead to "carbon leakage," shifting dirtier manufacturing to places where it is not accountable.

· Individual Accountability: Finally, students debated individual-level carbon accountability (taxes or carbon budgets). The instructor shared the perspective that many problems are system problems, not individual choice problems, citing the small emission reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown.

2. Water Stress in Context (Water 101)

The class started by establishing the foundational facts about water distribution, scarcity, and use:

· Water Abundance vs. Scarcity: While the Earth is abundant (70% water), only 2.5% is freshwater, and two-thirds of that is locked in glaciers.

· Water Distribution and Governance: Student H highlighted the problem with national averages, noting that water is fundamentally local and requires granular, sub-national data.

· Student I from Lima shared a powerful example of unequal distribution, where some neighborhoods have water only three days a week or must pay trucks high prices for delivery.

· The instructor shared the New York Catskills example as a template for managing risk, where investing in upstream farm interventions was far cheaper and more durable than building a multi-billion dollar end-of-pipe filtration system.

· The class discussed how power and governance override hydrology, citing Phoenix, Arizona, a desert city that imports massive amounts of water, versus Ethiopia, where 84% of the Nile originates, yet faces massive water scarcity due to lack of financial resources and infrastructure.

· The collapse of the Aral Sea was used to illustrate how policy (a shift to irrigation-intensive cotton farming after the Soviet Union dissolved) drove water scarcity, rather than natural factors,

· Water Use and Embedded Water: About 70% of human water use is in agriculture. The concept of embedded water was introduced, noting that dry products (like a cotton T-shirt or a car) require massive amounts of water to produce the raw materials.

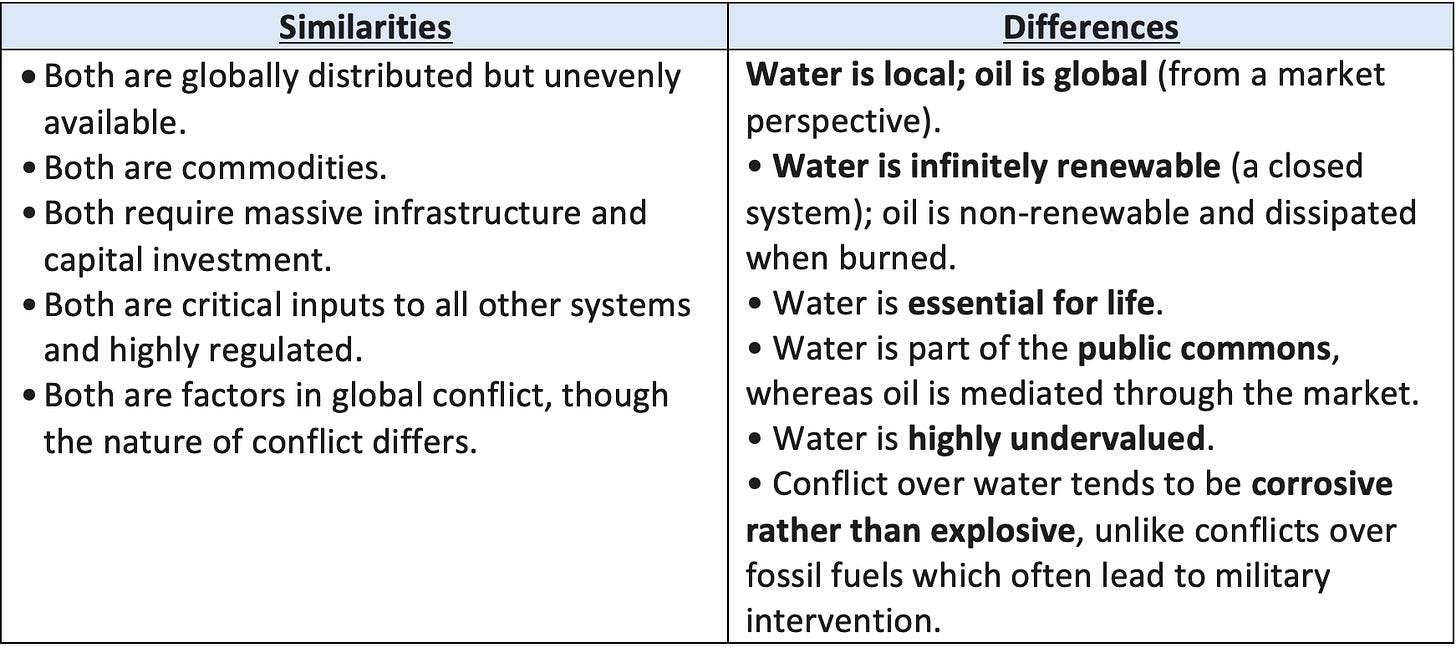

3. Water vs. Oil Discussion

The in-class breakout session explored the popular comparison of water to "the oil of the 21st century".

4. The Coca-Cola Case: Strategy and Managerial Choices

The class focused on Coca-Cola's shift from being defensive about its water use (following protests in India) to proactively managing water as an enterprise risk. The core insight derived from Coca-Cola's risk assessment was that the plant efficiency metrics they traditionally tracked ranked low in explanatory power for true enterprise exposure.

· Risk Assessment and Strategic Shift: The new strategy was driven by risk modeling that quantified six categories of risk (Watershed, Supply Reliability, Efficiency, Supply Economics, Compliance, Social/Competitive). This systemic analysis provided the "empirical basis for deciding where you going to put finite resources to try to mitigate risk". The overarching strategy involved intervening at the watershed level—moving "upstream"—to benefit not just the company but also the community ("leaky" interventions).

· Debating Water as a Human Right: The class watched excerpts from a film featuring the former CEO of Nestlé, who argued that water should have a value (not be a human right).

· Student J pointed out the business reason for this view, noting that the CEO's portfolio is large chunk of bottled water.

· Students argued that water is necessary for the right to live in dignity and that if it is a human right, governments should be mandated to provide it.

· The key tension articulated was: If water is a human right, who bears the responsibility and cost of delivering it across distance and infrastructure?

· Student K suggested that Coca-Cola, as a large brand, has the power to push for water availability while still running its business.

Strategic Options Analysis and Student Insights:

The class assessed three strategic options for Coca-Cola's future water strategy:

1. Replenishment 2.0: Focus volumetric projects in the same watersheds where extraction occurs ($40M cost).

2. Upstream Shift: Redirect resources to farmer practices, irrigation efficiency, and watershed restoration in critical sourcing regions ($150M cost).

3. Science-Based Targets (SBTN): Pilot basin-context targets, requiring new data systems and local partnerships ($75M cost).

The consensus (center of gravity) among students favored the Upstream Shift path, prioritizing basin-level and supplier interventions.

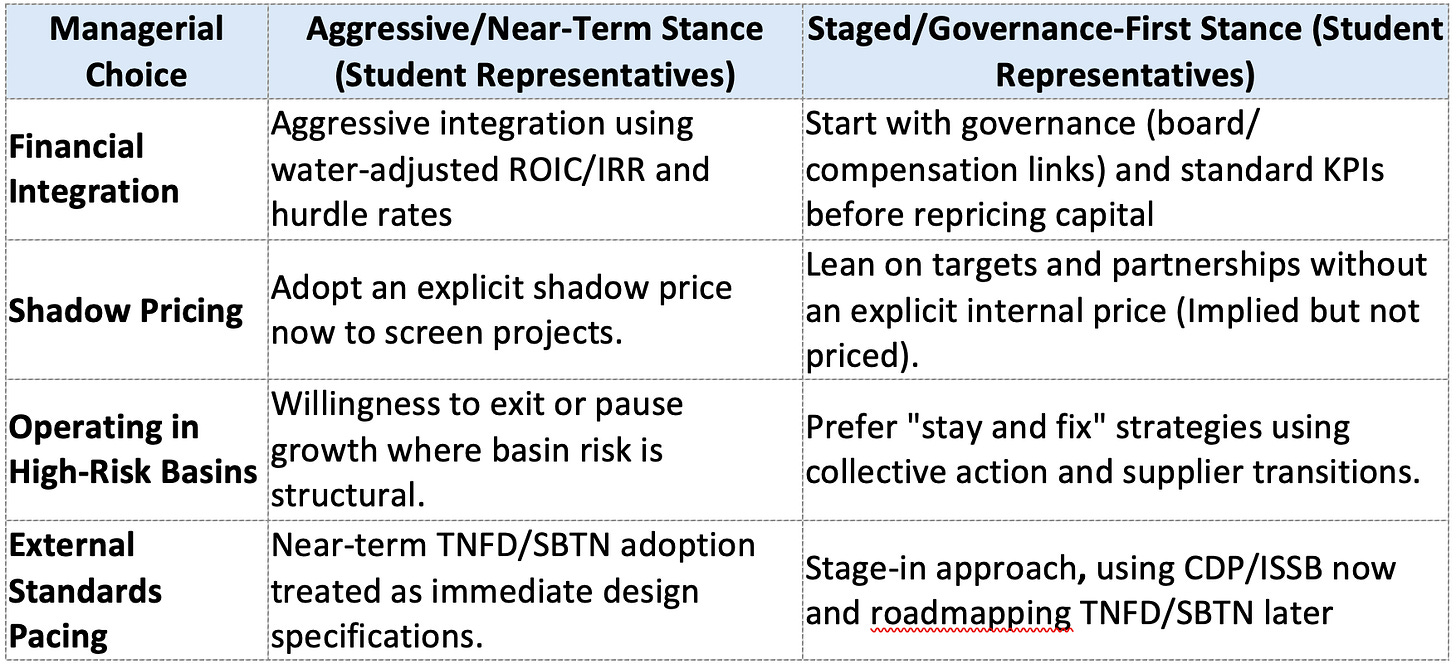

Areas of Productive Disagreement (Student Divergences): The student responses surfaced several key managerial debates:

The ultimate composite operating picture concluded that credible action requires ranking basins by business exposure, shifting capital upstream where risk-reduction per dollar is greatest, and ensuring governance provides the spine (board visibility, incentive links, and clear ownership splits).